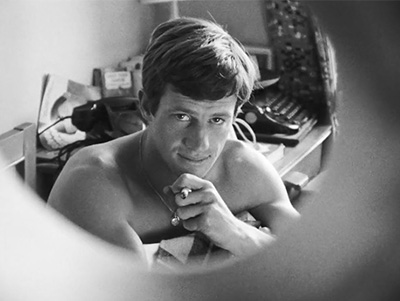

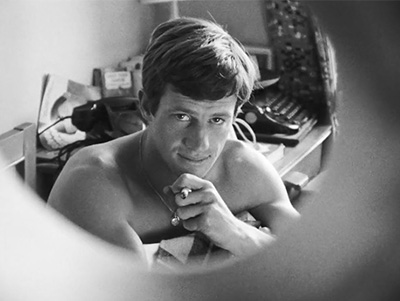

در قیاس با رفقای موجنوییاش کاراکتری شوختر داشت؛ و مکارتر. میشل را هم اوّلین نفر خودش به پلیسها فروخت (دقیقهی 55) و آخرِ کار گناهش را انداخت به گردنِ پاتریشیا. اساساً -روراست اگر بگویم- علت مطلوبتر بودنِ کارهای او برای من، در مقایسه با سایرین، بالاخص جدیترهایی چون تروفو، در همین نکته خلاصه میشود: با اخلاق نبودنش!

بیآییم در ذهنمان دو فیلم مطرحی که از پیشگامان موج نوی سینمای فرانسه به شمار میآیند، «از نفس افتاده» و «چهارصد ضربه» را، کنار یکدیگر قرار دهیم و رویکردهای کلیشان نسبت به سینما را، لیست کنیم؛ چه بهدست میآوریم؟ هدفْ قیاسِ خوبی و بدی و بهتری و بدتری و وزن کردن و متر کردنشان نیست و بنده هم این منظور را ندارم که دوستداشتنی بودنِ ساختهی تروفو را کتمان کنم –از آنجایی که آثار گدار را بیشتر میپسندم-؛ نه، که اتفاقاً «چهارصد ضربه» هم فیلمی خوشساخت و خلاقانه است و در این شکی نیست، اما جنسِ کارِ نو کردن و دیدِ خلاقانه داشتن در ساختهی تروفو، بهعقیدهام، بسیار متفاوتتر از رویکردهای گدار به این مقولههاست و این تفاوت بهزعم نگارنده از شیوهی خاص هر فیلمساز در نگرش به مفهوم سینما نشأت گرفته است –و نه صرفاً علاقه به کار کردن در یک کتگوریِ شخصی-؛ و شاید در ذاتِ این نظر -بااحتیاط باید بگویم که- ایدهای نهفته است دربارهی بهکارگیریِ از مؤلفهی شوخی در فیلمهای این دو کارگردان. شوخیای که البته به یک تعریفِ ساده و متداول محدود نمیشود و هر کدام از دو فیلمسازِ فوقالذکر هم با تعریفی مختص به خودشان میفَهمَندَش و از آن -در صورت لزوم- استفاده میکنند.

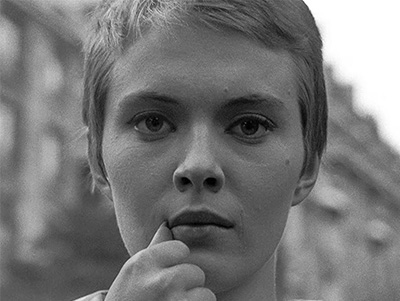

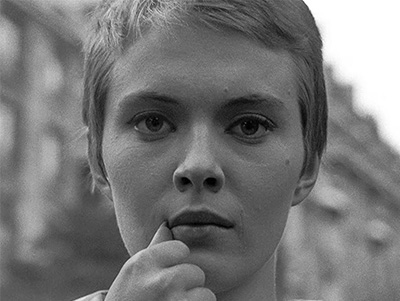

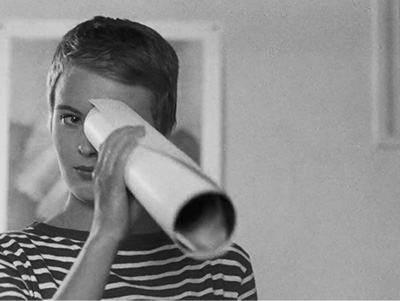

در «چهارصد ضربه»ی تروفو، هنگامی که آنتوان از پدرش هزار فرانک میخواهد و پدرش به او میگوید «اگه هزار فرانک میخوای پس یعنی امیدواری پونصد تا گیرت بیاد پس واقعاً سیصدتا لازم داری پس بیا این صدتا رو بگیر» ما اساساً پیش از کمدی و مهمتر از نوع کمدی، با یک مسئلهی اخلاقی طرف هستیم؛ سردی روابط میان اعضای خانواده و رواج دروغ و بیاعتمادیِ موجود در کوچکترین لایهی اجتماع که در قالب یک بازیِ زبانی بیان میشود و تنها هم به لبانِ پدرِ خانواده است که لبخند میآورد و نه کس دیگر -بامزه بود ولی شوخی نبود!-. اساساً کارهای تروفو با هر دیدگاهی که بررسی شوند و هر نکتهی فرعی و اصلیای که بتواند پیوستشان شود، در انتها همهی راههای جانبی را به یک شاهراهِ ارزشی میرسانند و مخاطب را میبَرند به لبهی یک تصمیمگیری؛ تصمیمگیری بهعنوان کنشی اخلاقی و مدنی و تلنگری به تمدنِ کوچکِ درونِ هر فرد. اما از آنطرفْ بازی زبانی در «از نفس افتاده» چهقدر اخلاقیست و مدنی وقتی مثلاً میشل نامِ پاتریشیا را با صدایی دورگه و بهشکلی بخشبخشگونه میگوید «Pa-tri-cia» و سپس پاتریشیا از پشت پرده ظاهر میشود و دامنِ پیراهنِ راهراهش را روی اُکابه میاندازد و بخشبخش جواب میدهد «Qu’est-ce-qu’il-y-a»؟ (دقیقهی 80)

کدامیک از شوخیهای «از نفس افتاده»ی گدار نکتهای داشتند متعالیتر از حالتِ سادهی یک شوخی یا یک مسخرهبازی یا یک اَدا؟

گفتگوی پاتریشیا با نویسندهی ناشناس را به یاد بیآورید؟ همان نویسندهای که نقشش را ژان-پیر ملویل بازی کرده بود. پیش از نمایش جلسهی مصاحبه، میشل در حال اَدا در آوردن به پاتریشیاست و ملویل -که هنوز او را نمیشناسیم و ندیدیم- از کنار میشل رد میشود؛ شوخی کوچکیست البته و در تماشای اوّل ِ فیلم شاید کسی حتی متوجهاش هم نشود، اما همین شوخی کوچک، از چه جنسیست؟ تصادف است دیگر. اخلاقی که نیست؟ هست؟ یک بازیگوشی -از سمت گدار- و یک اَدا درآوردن -از سمت میشل-؛ Comedy Farce شاید.

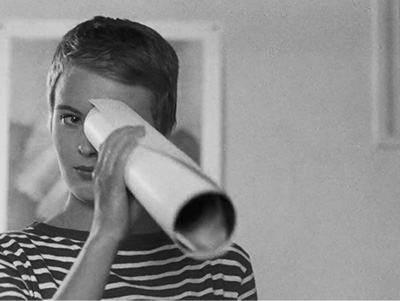

اَدا در آوردن در «از نفس افتاده» که برای خود دنیایی مستقل و منحصر به فرد دارد! بارها تکرار میشود، توسط افراد مختلف، و نه آنقدری بامزه است که بگوییم «از نفس افتاده» کمدیست و نه آنقدری هم یخ و اتفاقی و نالازم که بتوانیم نادیدهاش بگیریم (اگر کاملاً بیهوده بود که گدار حذفش میرد! نمیکرد؟ او که از سلاطینِ حذفیات است!).

مردی با بُردی در دستْ جلوی پاتریشیا را میگیرد و بعد از بیاعتنایی پاتریشیا به او، مرد پشت به پاتریشیا -و رو به دوربین- اَدای مسخرهای را درمیآورد (دقیقهی 11)؛ همان مرد بار دیگر در کافهای ظاهر میشود و سرِ میزِ پاتریشیا پشتِ به زنی دیگر شروع به اَدا در آوردن میکند (دقیقهی 78).

و یا اَدا درآوردن لابیگِرلِ هتل به همکارش -که با میشل سر و سرّی داشت- (دقیقهی 18) و یا اَدا درآوردن دختری که در خیابان از میشل میپرسد “آقا! شما مشکلی با جوانها ندارید؟” (دقیقهی 13).

مرتبطترین و جالبترین اَدا بهنظرم مختص خود میشل است؛ وقتی که در اتاق دوستِ دخترش (دقیقهی 8 فیلم) میگوید که میتوانسته هنرپیشه شود و سپس دهانش را در آینه بهطرز اغراقآمیزی باز و بسته میکند و انگار که مشغول زدن حرفی باشد؛ این حرکت را بعدتر (دقیقهی 29) میشل به پاتریشیا یاد میدهد و پاتریشیا رو به آینه آن را تقلید میکند؛ در نهایت در پایانِ فیلم هنگامی که میشل تیر میخورَد، رو به پاتریشیا، همین حرکت را مجدد تکرار میکند و انگار که باز هم دارد حرفی به او میزند. پس از آن هم میشل برای نشان دادنِ مرگِ خودش، خودش دستش را میگذارد روی صورتش و چشمانِ خودش را میبندد! و بعد پاتریشیا رو به دوربین دستانش را روی لبهایش میکشد و اَدای ژستِ بوگارتی میشل را درمیآورد! حرکتی که میشل در طول فیلم به تقلید از هامفری بوگارت چندمرتبهای تکرار کرده بود!

کمی فکر کنیم: این اصرار بر شوخی کردن، این پافشاریِ بر به سخره گرفتنِ هر چیز، حتی در اوجِ قصه و در لحظهی مرگِ کاراکترِ اصلی، آیا در فیلمهای غیرکمدیِ ساختهشده پیش از «از نفس افتاده»، رخ داده بود؟

میشل در «از نفس افتاده» چگونه مرگ خود را رقم زد و کاترین در پایان «ژول و ژیم» ِ تروفو چگونه مرگ خود را رقم میزند؟ بهواقع باوجودِ اینکه «ژول و ژیم» از معدود آثار تروفوست که پیرنگ در آن کمترْ چارچوبزده بهنظر میآید و بازیگوشتر رفتار میکند -در کنار «شبِ آمریکایی»- ولی باز هم همچنان در یک نگاهِ کلیْ خلاقیت داشتن در «ژول و ژیم» به تعبیر من نهایتاً تروفو را تبدیل میکند به یک بانشاطِ غمگین و فقط همین. گدار اما برای من، دنیا همه هیچ و اهل دنیا همه هیچتر است و من این را بیشتر میپسندم؛ سرخوش است و سبکسَرتَر؛ بیهیچ جدیتی. هنگامی که کاراکترهایش در «تفنگداران» به جنگ میروند هنگام خداحافظیْ یکی از زنها به شوهرش میگوید که از جنگ برایش -سوغات- بیکینی بیآورد و میدانید… شوخی بود اما خیلی هم دور از ذهن و غیرمنتظره نبود؛ مگر نه؟ گدار بهقدری خودش با آثارش سرِ شوخی دارد و غیرمهم جلوهشان میدهد که واقعاً کاراکترهاش ظرفیت این را دارند که حتی از جنگ برای هم -سوغات- بیکینی بیآورند!

و فکر میکنم که حتی تکنیکهایی مثل نماهای نصفهای که در «از نفس افتاده» میگرفت و اینکه گاهی از زاویهای فیلمبرداری میکرد که انگار بخشی از صحنه درونِ تصویر وجود ندارد و یا اینکه هر جا که مِیلش میکشید کات میزد و شد خالق مفهومی به اسم جامپکات و غیره، از همین سرِ شوخی داشتنِ او و بیخیالیاش میآمد؛ عامدانه درک مخاطب از فضا و زمان را به بازی میگرفت -دهنکجی میکرد به آن درواقع- و برایش اهمیتی نداشت اگر چیزی را در جایی که کسی انتظارش را نداشت رها کند -وقتی ذهن مخاطب این رهایی را نمیپذیرفت- و به چیز دیگری بپردازد -آنچه که لاجرم فرم در وهلهی اوّل نامفهومش میکرد-.

اتفاقاتِ عجیبِ بصری که در فیلم فراوان است البته و اطمینان دارم که مخاطبِ این نوشته نیز به وجودشان واقف است؛ پس اجازه دهید تعدادی از آنها را که بیشتر به کنشِ “شوخی کردن” طعنه میزنند را بهعنوان نمونه مثال بیآورم تا به کمک آنها بتوانم -شاید که- منظورم را دقیقتر منتقل کنم.

در شروع فیلم صدای میشل پیوسته است و منطبق با زمانِ خطی، اما تصاویری که فیلمساز به مخاطب نشان میدهد به مکانهای متفاوتی کات میشود و از جریانِ پیوستگیِ زمانْ خارج.

تقریباً در دقیقهی 52 که میشل در حال دزدیدن ماشین است، حین دزدی، فیلمساز کات میکند به سکانسی دیگر؛ سکانسِ دیگری که میشل ماشینِ دیگری را میبیند و آن ماشین را دقایقی بعدتر میدزدد. بهواقع فیلمساز دزدی اوّل از ماشین اوّل را با کاتْ رها میکند؛ ما فقط میبینیم که کسی به میشل نزدیک میشود و میرویم به سکانس بعد! خب قبلی چه شد؟ دزدیِ میشل ناموفق بود؟ با آن مرد غریبه که گویا صاحبِ ماشین بوده کار به درگیری کشیده شده؟ میشل از چه زمانی ماشین را از دست داده (همانموقع یا بعدتر؟). اصلاً چرا فیلمساز دزدیِ ناموفقی را به ما نصفه نشان داد؟ مگر سینما بُرشِ سِلکتشدهای از یک کیک نبود و با حذفکردن به پسندِ مخاطب درنمیآمد؟

یا در دیالوگها، تقریباً در دقیقهی 11 پاتریشیا از میشل دربارهی اتفاقاتِ مدتی قبلْ میانِ خودشان سؤالی میپرسد و میشل هم پاسخ میدهد و هیچ نشانهای برای مخاطب برای کشف قصه و گذشتهی این دیالوگها وجود ندارد؛ انگار که فیلم از وسط شروع شده باشد! کدام روز؟ کدام اتفاق؟ کدام ناراحتی؟ سرِ چه؟

در میان این شوخیها، اِرجاع مستقیم فیلم به «چهل تفنگ» ساختهی ساموئل فولر و بازسازی سکانسی از آن توسط میشل و پاتریشیا هم در جای خودش کاملاً شوکهکنندهست (دقیقهی 37).

از دیگر شوخیهای سینماییِ فیلم نمایش پوستر «ده ثانیه تا جهنم» ساختهی رابرت آلدریچ بود (دقیقهی 13) که بلافاصله بعد از نمایش پوسترْ فیلمسازْ جوانِ مُردهای افتاده بر کفِ خیابان را به ما نشان میدهد و میشل هم برای ثانیههایی همراه با مردم میرود به بالای سرِ مَردِ مُرده! عینِ سرنوشتی که پایان فیلم برای خودش رقم میخورد (مُرده، بر کفِ خیابان و مردم به دور او) و حالا پیشبینی این اتفاق در شروع فیلم، همراه با نمایش عبارت «ده ثانیه تا جهنم» چیزیست جز احضار زودهنگامِ پایان فیلم و ده ثانیه تا به جهنم رفتنِ میشل؟

مثالی دیگر اینکه گدار در مصاحبهش با مجلهی کایهدوسینما (شماره 138) میگوید که شخصیت پاتریشیا با بازی جین سیبرگ ادامهی کاراکترِ اوست در فیلم «سلام بر اندوه» ساختهی اُتو پِرِمینجر! و در ابتدا قصد داشته است که «از نفس افتاده» را با نمایش آخرین سکانس «سلام بر اندوه» آغاز کند و بعد از اتمامِ آن سکانس روی پرده بنویسد که “سه سال بعد” و سپس نمایشِ اوّلین نمای فیلمِ جدید!

شوخیها بیشتر از این تعدادیست که ذکر کردم اما خب کوتاه میکنم؛ در هر حال هم از نظر کمیتی زیادند و هم از نظر کیفیت قابلتوجهاند!

نمونهی مشابهِ این نوع از شوخی کردن با سینما و اِلمانهای سینمایی را، که امروز به انواعی از آنها اِرجاع هم میگوییم، آیا در آثار فیلمسازان دیگری که پیش از گدار فیلم میساختهاند، دیده بودید؟ آوانگاردیسمِ ساختاریای که سر شوخی داشته باشد البته پیش از گدار به شکلهای متفاوتترِ دیگری وجود داشته است و حرفی در این نیست؛ اما برای مثال مقایسه کنید آثار گدار را با آثار یاساجیرو اُزو که او هم از بزرگانِ “شوخی کردن” در سینماست بهنظرم! اُزو هم نسبت به فرمْ منعطف و سبکسرانه رفتار میکند و درزمانهایی نسبت به انتظار مخاطب و عاداتِ او، شوخیهایی را انجام میدهد تا سببی شود براینکه تماشاگر را متعجب و یا گیج کند؛ منتهای مطلبْ حداقل در ذهنِ من، شوخیهای اُزو بسیار باوقارتَر و بهجاتَر هستند در مقایسه با جرقههای سریعِ ذهنِ گدار؛ اُزو بسان پدربزرگیست دنیادیده که سعی میکند مخاطبانِ کمتجربهاش را قلقلک دهد، ولیکن گدار بیشتر شبیه کودکی سربههواست که هر لحظه امکان دارد با رها کردنِ دستش گمش کنیم! آن کودکی که جنبهی قلقلک دادن را هم ندارد و ما -به اشتباه و نادانسته- با باز کردنِ سرِ شوخیْ با او و پذیرشِ آن، این فضا را به او دادهایم که کل خانه را بههم بریزد! عجیب نیست که چنین آدمی اسم فیلمش را بگذارد «از نفس افتاده»! هم دیدِ فیلمساز است نسبت به آنچه که تجربه کرده و آن مفاهیمی که آموخته و دیگر حوصلهی هیچکدامشان را ندارد، و هم خستگیِ مفرط کاراکترهای فیلمش نسبت به اطرافِ خود و جامعه و داشتنِ همین دیدگاهِ بیاعتنا و بیقید نسبت به مسائل و رخدادها و حتی نسبت به جانِ افراد.

اما نکته کجاست؛ آثار گدار، باوجود اینکه مشخصاً کمدی نیستند، اما میشود گفت که یک شیرین بودنِ خاصی درونشان حس میشود؛ مثل همین ارجاعاتی که جملگی لبخند به لبِ مخاطبِ آشنا با سینما میآورند. یا شیرین بودنی که اصلاً ربطی به ماجراهای فیلمها ندارد و بیشتر با نحوهی ارائهی فیلمساز و بازیهای گوشه و کناریِ فرمالِ فیلمِ او گره خورده است (پات-ری-شیا/کیس-کی-لیا (رجوع به ابتدای مقاله)). این شیرین بود مسببیست که فیلمهای گدار هرچهقدر هم که عجیب و ساختارشکن بهنظر رسند، اما برای مخاطبْ جذاب و قابلفهم تلقی شوند. و این شیرینی برای من، امروز که سالها از آن سالها میگذرد، میشود: پستمدرنیسم پیش از پستمدرنیسم.

مروری داشته باشیم بر به قولِ خودش Histoire(s) du cinéma: شکلگیری مدرنیسمِ دوّم، در تاریخ سینما، بهطور تقریبی از میانهی دههی 1950 آغاز میشود و تا میانهی دههی 1980 ادامه مییابد. مدرنیسمِ اوّل قاعدتاً بهزمانی دورتر برمیگردد و به دورانی اشاره دارد که هنر سینما بهتازگی متولد شده بود؛ مدرنیسمِ اوّل موازی با مدرنیسمِ درجریانِ هنرهای دیگر -در آن روزگار-، توسط فیلمساز/نظریهپردازانی خاص شکوفا شده بود و هر از چندی هم آثار خیرهکنندهای را به جهان عرضه میکرد. مدرنیسم اوّل بهزبانی دیگر شاید بشود گفت که ترجمهای بود، ترجمهای از هنرمندانی که هر یک به نحوی میکوشیدند از عناصر و دیدگاههای مدرنیسمِ مثلاً در نقاشی یا مدرنیسمِ مثلاً در موسیقی استفاده کرده و با هنر نوظهورِ سینما سازگارشان کنند. فیلمهایی مثل «سمفونی مورّب» محصول 1924 به کارگردانی وایکینگ اِگلینگ، یا «ستارهی دریایی» محصول 1928 به کارگردانی مَن رِی و فیلمهای دیگری که اینجا محل صحبتِ ما نیستند؛ مدرنیسمِ اوّل، بهعقیدهی من، از آنجا که برای سینمای تازهپاگرفته بیگانه به حساب میآمد و خیلی زود و ناگهانی خود را مشغول کرد به کنکاش در مفاهیم سینمایی و ثبت نظریه و مانیفست، پس زده شده و با سرعتِ سریعی که اِستارت زده بود پیش نرفت و عقب ماند و وقتی چیزی پیش نمیرود و ادامه ندارد طبیعتاً دوران پسابعدِ خودی هم ندارد که بشود مثلاً پسامدرنیسم (لازم به ذکر است که بنده بهشخصه از طرفدارانِ مدرنیسم اوّل هستم). مدرنیسم دوّم اما جایی رخ داد که سینما طی دههها به رشد مشخصی رسیده بود و دورانهای کلاسیکِ متفاوتی، و مکتبها و نظریاتِ مرور شده و نقدشدهای را، و کتبِ خواندهشدهای را پشت سر گذاشته بود و حالا بود که فیلمسازانی چون برگمان، یانچو، تِشیگاهارا، فاسبیندر و غیره، از دلِ تاریخِ خودِ سینما، ظهور پیدا کرده بودند. فیلمسازانی با فیلمهایی سخت و برای فهمشدنْ ثقیل. فیلمهایی پیچیده که فرمشان نیازمند کشف کردن و تقلای دائمیِ مخاطب بود و گاهی اوقات هم که اصلاً هیچگاه بهطور کامل فهمیده نمیشد؛ مانند فیلمهای بعدترِ خود گدار که مشخصاً چنین آثاری بودند.

پستمدرنیسمها اما، جاماندگان از مدرنیسم بودند. فیلمسازانی که هوش و ذکاوتشان چیزی کم از مدرنیستها نداشت ولی نیازی هم نمیدیدند که یک «شب» دیگر یا «آینه»ای دیگر بسازند -شاید به این دلیل که سرریزِ مدیا از تلویزیون بسیاری از مفاهیم را بیاعتبار کرده بود-؛ ترجیحِ فیلمسازان پستمدرن بیشتر اِرجاع دادن به هنر و سینما بود، اَدای دِین کردن و در مواردی هم شوخی کردن و بازی کردن. پستمدرنیستها با اعتدالی بیشتر، با صبری بیشتر -برای مخاطبی تنبلتر-، و البته با افراطگرایی کمتر و ادعایی کمتر، مخاطبین را دوستانهتر به سمت خود میخواندند -بهعوضِ پس زدنِ بیننده چُنانِ مدرنیستها-؛ و بیشترْ -از مدرنیستها- به ارائهی قصهای فکر میکردند که مخاطب بتواند بعد از پایان فیلم خلاصهاش را برای دوستانش “تعریف” کند.

حال اشارهی بنده به این جریانها از این جهت است که مشاهده و مطالعه و جمعآوری دادههای نگارندهی این نوشتار، طی سالها، این اجازه را، گویی میتواند به من بدهد که مدعی شوم گدار پیش از اواسط دههی 1980، یعنی پیش از سالهایی که از نظر تاریخی پستمدرنیسمها تازه شروع به پر و بال گرفتن کرده بودند (هرچند که آنزمان چنین نامی رویشان گذاشته نشده بود)، با اوّلین فیلم بلند خود، با «از نفس افتاده»ی خود، در سال 1960، ردپایی از پستمدرنیسم را در جادهای خالی و در دستِ تاسیس، از خود بهجای گذاشته بود.

گدار هرچند بعدتر محصور و وابستهی مدرنیسم شد و تغییر مسیر داد، اما در دورانی که بهباورِ من خوشفکرتر بود و آثار برجستهتری هم خلق میکرد، درکی شاید بداهه از پستمدرنیسم را در ذهن خود پرورش داده بود و با دوری از دشواریت و ادعایی بر زیر و رو کردن سینما -آنچه مدرنیسم به آن علاقه داشت-، به نخبهگرایی در فیلمهایش لباسِ دلقک پوشانده بود.

هدف، در اینجا، در این پستمدرنیسمِ خاص و بَدوی، نیتها نیستند. هدف تنها کنار هم قرار دادنِ اجزاست بهشیوهای دلپذیر و هوشمندانه.

در شروع فیلم، میشل، شخصیت اصلی فیلم، دختری را غال میگذارد و ماشینی را میدزدد و میرود. در داشبوردِ ماشینِ دزدیده شده تفنگی وجود دارد. میشل بدون هیچ دلیلِ بُلدشدهای از جانب فیلمساز، با همان تفنگ کسی را میکشد. این حادثهی محرکِ کاملاً اتفاقی برای میشل، در وهلهی اوّل پشت کردن به نگاه عِلّی و معلولی کلاسیک است. تفنگ اینجا، به عبارتی، توسط فیلمساز در داشبورد قرار داده شده است (دقیقاً با همان رویکردی که هانهکه در «بازیهای مسخره» کنترلِ بهعقب گرداندنِ فیلم را برای قاتلین زیرِ مبل پنهان کرده بود). درانتهای فیلم، الگوهای آغاز فیلم تکرار میشوند: میشل اینمرتبه غال گذاشته میشود -خیانتِ پاتریشیا- و بهوسیلهی تفنگِ کسِ دیگری کشته میشود (میشل: پلیس/پلیس: میشل). هم در آغاز و هم در پایان، ما دستِ رفته بر اسلحه را میبینیم اما لحظهی شلیک گلوله -به پلیس و به میشل- را نمیبینیم.

اگر من هم بخواهم به آغاز نوشتهی خودم رجوع کنم، میتوانم باز از تروفو اسم ببرم و بگویم که اگر تروفو بود، طوری این اتفاقات را، این قطعات پازل را، کنار هم میچید، که ذهنِ مخاطب را سوق دهد بهسمت دنیا و دارِ مکافات و ارزشهای ازدسترفتهی روزگار! اما گدار با ایدهها، و ابتکار خود، به چنان طریقی قطعات پازل را کنار هم میچیند که معنا کنار میرود و درنهایت این تنها فرم است که باعث میشود تماشاگر با خودش بگوید: چه جالب!

فرمی که پیچیدگیهایی دارد اما آن را با صدای بلند فریاد نمیزند و در سایه، مخاطب را فقط خنک میکند: پستمدرنیسم.

آنچه خواندید یکی از پنج نوشتاری بود که طی پنج هفته، دربارهی «از نفس افتاده»ی گدار، برای خود و در خلوتِ خود، اِتود زدم و در وبِ شخصیام منتشر کردم.

برای مشاهدهی هر یک از این یادداشت/تمرینها روی عنوانشان در خطِ پایین کلیک کنید:

تمرین «از نفس افتاده»گی/ هفتهی اوّل: جذابیتهای پنهان غیربورژوازی

تمرین «از نفس افتاده»گی/ هفتهی دوّم: ژان-لوک گدار و تالار اسرار

تمرین «از نفس افتاده»گی/ هفتهی سوّم: یک مردِ کمی جدی

تمرین «از نفس افتاده»گی/ هفتهی چهارم: کشتن سینمای مقلد

تمرین «از نفس افتاده»گی/ هفتهی پنجم: پاریس، جزء به کل

In comparison to his Nouvelle Vague friends, he had a more humorous and more cunning character. He was also the first to sell Michel to the police (55th minute), and in the end, he placed the blame on Patricia. Essentially—if I’m being honest—the reason his works are more desirable for me compared to others, especially the more serious ones like Truffaut’s, is summed up in this point: his lack of morality!

Let’s place two prominent films, ‘Breathless’ and ‘The 400 Blows’, which are considered among the pioneers of the French New Wave, next to each other in our minds and list their general approaches to cinema. What do we get? The goal is not to compare good and bad, better and worse, or to weigh them against each other, nor am I intending to deny the likability of Truffaut’s creation—since I prefer Godard’s works—but no, ‘The 400 Blows’ is, of course, a well-crafted and creative film, without a doubt. However, in my opinion, the kind of innovation and creative vision in Truffaut’s work is very different from Godard’s approach to these matters. This difference, in my view, stems from each filmmaker’s unique way of looking at the concept of cinema—not just their preference for working in a personal category. And perhaps, embedded in this view—cautiously, I must say—there is an idea about the use of humor as a feature in the films of these two directors. Humor, of course, is not limited to a simple, conventional definition, and each of the two filmmakers mentioned has their own specific understanding of it, which they use—if necessary.

In Truffaut’s ‘The 400 Blows’, when Antoine asks his father for a thousand francs and his father replies, “If you’re asking for a thousand, then you’re hoping to get five hundred, so you actually need three hundred. Here, take this hundred,” we are essentially faced with an ethical issue before comedy, and more importantly, before the type of comedy. The coldness in familial relationships and the prevalence of lies and distrust in the smallest layers of society are conveyed through a linguistic game. Yet this only brings a smile to the lips of the father and no one else—it was funny but not a joke! Fundamentally, no matter how you analyze Truffaut’s works, or what primary or secondary elements you might attach to them, they all ultimately lead to a single ethical main road. They guide the audience to the brink of a decision—a decision as an ethical and civic act, a nudge toward the small civilization within each individual.

But on the other hand, how ethical or civic is the linguistic play in Godard’s ‘Breathless’? For instance, when Michel pronounces Patricia’s name with a half-muted, segmented tone, “Pa-tri-cia” and then Patricia emerges from behind the curtain, throwing the striped hem of her dress over Okabe and responds in a similarly fragmented way, “Qu’est-ce-qu’il-y-a?” (80th minute).

Which of the jokes in Godard’s ‘Breathless’ held any notion more elevated than the simple state of a joke, a ridicule, or a pretense?

A man holding a board stops Patricia in her path, and after she ignores him, he turns his back to her—facing the camera—and performs a ridiculous pretense (minute 11). The same man reappears later in a café, seated near Patricia, and begins pretending again, this time behind another woman (minute 78).

Or take the pretense of the hotel lobby girl directed at her colleague—someone with whom she had a personal history and familiarity, someone who shared a connection with Michel (minute 18). Or the pretense of the young woman on the street who asks Michel, “Sir! You’ve nothing against youth?” (minute 13).

The most intriguing and relevant pretense, in my opinion, belongs to Michel himself. In his girlfriend’s room (minute 8 of the film), he declares he could have been an actor and then dramatically opens and closes his mouth in front of the mirror as though saying something profound. Later (minute 29), Michel teaches Patricia the same gesture, and she imitates it in front of the mirror. Ultimately, at the end of the film, when Michel is shot, he repeats the same gesture, facing Patricia, as though he is once again trying to say something to her. Afterward, Michel demonstrates his own death by covering his face with his hand and closing his own eyes. Then, Patricia turns to the camera, runs her hand across her lips, and mimics Michel’s Bogart-like gesture—a movement Michel had repeated several times throughout the film, imitating Humphrey Bogart.

Let’s think for a moment: this insistence on joking, this persistence in ridiculing everything, even at the height of the story and in the main character’s death scene—had such a thing occurred in non-comedy films made before ‘Breathless’?

How did Michel in ‘Breathless’ bring about his own death, and how does Catherine in the end of ‘Jules and Jim’ by Truffaut bring about hers? In fact, although ‘Jules and Jim’ is one of the few works by Truffaut where the plot seems less constrained and plays more freely—along with ‘La Nuit américaine’—still, in a broader sense, the creativity in Jules and Jim, in my view, ultimately turns Truffaut into a cheerful yet sorrowful figure, and that’s all. But Godard, for me, “the world is all nothing, and the people of the world are even more nothing” (the equivalent of the English idiom “Nothing matters in the grand scheme of things”), and I prefer this; he is carefree and more lighthearted, without any seriousness. When his characters go to war in ‘The Carabineers’, one of the women, while saying goodbye to her husband, tells him to bring back a bikini from the war as a souvenir—and you know… it was a joke, but it wasn’t all that far-fetched or unexpected, was it? Godard has such a playful relationship with his works, making them appear unimportant, that his characters genuinely have the capacity to bring back bikinis from the war for each other!

And I think even techniques like the half-shots he used in ‘Breathless’—or filming from an angle that makes it seem like part of the scene is missing, or cutting whenever he felt like it—he became the creator of something like the jump cut, and so on—came from his playful attitude and carefreeness; he deliberately played with the audience’s perception of space and time—mocking it, in fact—and he didn’t care if something was left behind in a place where no one expected it—when the audience’s mind didn’t accept this abandonment—and then he would move on to something else—something that inevitably made the form initially unclear.

The peculiar visual occurrences abundant in the film are, of course, evident, and I trust the reader of this text is well aware of their presence. Allow me, then, to highlight a few of these moments—specifically those that lean toward the act of “playfulness”—as examples to better convey my point.

At the start of the film, Michel’s voice is continuous and aligns with linear time, but the visuals presented to the audience cut to different locations, breaking the flow of temporal continuity.

Around the 52nd minute, while Michel is stealing a car, the filmmaker cuts to another sequence: a scene where Michel spots a different car, which he steals moments later. Essentially, the filmmaker abandons the first theft mid-action with a cut. We only see someone approaching Michel, and then we’re abruptly taken to the next scene. So, what happened earlier? Was Michel’s first attempt unsuccessful? Did he have a confrontation with the man—presumably the car’s owner—who approached him? At what point did Michel lose the car (then and there, or later)? Why did the filmmaker even show us an incomplete attempt at theft? Wasn’t cinema supposed to be a carefully selected slice of the cake, crafted to cater to the audience’s preferences through omission?

Or in the dialogues—around the 11th minute—Patricia asks Michel a question about events that happened between them some time ago. Michel answers, but there are no clues for the audience to uncover the story or the context of these dialogues. It feels as if the film began in the middle of things! Which day? What event? What upset? About what?

Among these playful elements, the film’s direct reference to Samuel Fuller’s ‘Forty Guns’ and Michel and Patricia’s recreation of one of its scenes is utterly shocking in its own right (at the 37th minute).

Another cinematic jest in the film is the display of the poster for Robert Aldrich’s ‘Ten Seconds to Hell’ (at the 13th minute). Immediately after showing the poster, the filmmaker cuts to the body of a young man lying dead on the street, with Michel briefly joining the crowd gathering around him. This mirrors Michel’s own fate at the end of the film—dead, lying in the street, surrounded by onlookers. The early foreshadowing of this event, accompanied by the phrase ‘Ten Seconds to Hell’, seems to be nothing short of a premature invocation of Michel’s demise, his own ten seconds before descending into hell.

Another example: Godard, in an interview with Cahiers du Cinéma (no. 138), mentions that Patricia, played by Jean Seberg, is a continuation of her character from Otto Preminger’s ‘Bonjour Tristesse’! Originally, Godard intended to open ‘Breathless’ with the final scene from ‘Bonjour Tristesse’ and then, after it concluded, flash the words “Three years later” on the screen, leading directly into the first shot of the new film.

The cinematic playfulness extends beyond the examples I’ve listed, but I’ll keep it brief. These jests are both abundant in quantity and notable in quality.

Have you seen anything comparable to this kind of playful engagement with cinema and cinematic elements—what we now often call references—in the works of filmmakers preceding Godard? Structural avant-gardism with a playful edge existed before Godard, albeit in different forms, so there’s no debate about that. For instance, compare Godard’s works to those of Yasujirō Ozu, who, in my opinion, is also a master of cinematic “playfulness.”

Ozu, too, approaches form with a flexible, lighthearted attitude, occasionally subverting audience expectations and habits with jests that surprise or even perplex. But, at least in my mind, Ozu’s humor feels far more refined and mature compared to Godard’s rapid bursts of ideas. Ozu is like a seasoned grandfather, full of wisdom, gently tickling his less experienced audience to evoke a smile or provoke thought. Godard, on the other hand, feels more like a mischievous child, constantly getting into trouble, oblivious to everything around him, and on the verge of chaos at any moment.

That child isn’t even trying to amuse us; instead, by mistakenly opening the door to his antics and accepting his behavior, we’ve given him the space to turn the entire house upside down!

Is it any wonder that such a filmmaker would name his film ‘Breathless’? It encapsulates both the filmmaker’s perspective on what he has experienced and learned—and his exhaustion with all of it—and the sheer fatigue of his characters toward their surroundings, society, and life itself. It reflects a dismissive, indifferent attitude toward everything, including the lives of others.

But where lies the point? Godard’s works, despite not being outright comedies, carry a unique sweetness within them—something palpable, like those references that bring a smile to the face of viewers familiar with cinema. Or, sweetness that isn’t directly tied to the plot of the films but rather emerges from the filmmaker’s approach and his playful formal touches scattered throughout the film (Pa-tri-cia/Qu’est-ce-qu’il-y-a?, as mentioned earlier in the article).

This sweetness is what makes Godard’s films, no matter how strange or avant-garde they may seem, captivating and comprehensible for the audience. And for me, looking back today after all these years, this sweetness translates into: postmodernism before postmodernism.

Let us take a look at what he himself calls Histoire(s) du cinéma: The emergence of the “second modernism” in the history of cinema roughly begins in the mid-1950s and continues until the mid-1980s. The “first modernism,” naturally, dates back to an earlier time, referring to the era when the art of cinema had only recently been born. Parallel to the modernism evolving in other arts of that period, the first modernism in cinema blossomed through the efforts of specific filmmaker-theorists, occasionally producing astonishing works for the world to behold.

The first modernism, to put it differently, might be seen as a sort of translation—a translation carried out by artists who sought to adapt the elements and perspectives of modernism in, say, painting or music, to the emerging art of cinema. Films like ‘Symphonie Diagonale’ (1924) by Viking Eggeling, or ‘L’Étoile de mer’ (1928) by Man Ray, along with others not within the scope of our current discussion, exemplify this movement.

In my view, the first modernism, being somewhat alien to the nascent cinema, quickly became preoccupied with exploring cinematic concepts, formulating theories, and drafting manifestos. However, it didn’t sustain its momentum. It was pushed back, failing to advance at the rapid pace it had initially set. And when something doesn’t move forward or evolve, it naturally doesn’t produce a “post-era” for itself—there’s no “post-modernism” to follow. (It’s worth noting that I, personally, am a fan of the first modernism.)

The second modernism, however, emerged at a point when cinema had reached a certain maturity through decades of growth, traversing various classical periods, schools of thought, critiques, and readings. By this time, filmmakers such as Bergman, Jancsó, Teshigahara, Fassbinder, and others had emerged from the history of cinema itself. These were filmmakers whose works were challenging, intellectually demanding, and often difficult to grasp. Their films were complex, with forms that required constant effort and discovery from the audience—works that, in some cases, could never be fully understood. Such was the nature of Godard’s later films, which clearly belonged to this category.

Postmodernists, however, were the “left-behind” of modernism—filmmakers who had missed the bus, so to speak, simply because they hadn’t been born in time to be part of that era. These were creators whose intelligence and ingenuity were no less than those of the modernists, but who saw no reason to craft another ‘La Notte’ or another ‘Mirror’. (Here, I mean the works of Antonioni and Tarkovsky, respectively, and not generic references.) Perhaps this was because the overflow of media, particularly from television, had rendered many ideas obsolete.

Postmodern filmmakers preferred to reference art and cinema, to pay homage, and, at times, to playfully engage or even mock. With greater restraint, more patience (for an increasingly passive audience), and less extremism or less grandiose claims, postmodernists approached viewers more amicably—unlike the modernists, who often alienated their audiences. They also focused more on creating fictional narratives that the audience could “retell” to their friends after the movie ended.

My reference to these movements stems from years of observation, study, and data collection, which, I believe, allows me to argue that Godard, even before the mid-1980s—when postmodernism was just beginning to take shape (though it wasn’t yet labeled as such)—left traces of postmodernism with his very first feature film, ‘Breathless’, in 1960. It was as if, on an empty and yet-to-be-constructed road, Godard laid down the foundation for what postmodernism would later become.

Although Godard would later become entrenched in and devoted to modernism, taking a different path, during a period that I believe reflects his most inspired and impactful work, he cultivated an almost instinctive understanding of postmodernism. By distancing himself from the complexity and the grand ambition to revolutionize cinema—a hallmark of modernism—he cloaked the elitism of his films in the attire of a clown.

The goal in this specific, primitive postmodernism is not about intentions. The aim is merely to assemble the pieces in a way that is both clever and pleasing.

At the start of the film, Michel, the main character, deceives a girl, steals a car, and drives away. Inside the dashboard of the stolen car, there’s a gun. Without any overt justification from the filmmaker, Michel uses that gun to kill someone. This entirely random inciting incident marks a deliberate departure from the classical cause-and-effect narrative. The gun here, in a sense, has been placed in the dashboard by the filmmaker—much like how Haneke, in ‘Funny Games’, hid the remote control under the couch to allow the killers to rewind the film.

At the end of the movie, the patterns from the beginning repeat: this time, Michel is the one deceived—Patricia’s betrayal—and is killed by a gun (Michel: Police/Police: Michel). In both the opening and closing, we see a hand reach for the gun, but the moment of firing—the shots at the policeman and at Michel—remains unseen.

If I were to return to the beginning of my own writing, I could once again name-drop Truffaut and say that if it were him, he would have arranged these events, these puzzle pieces, in a way that guided the audience’s mind toward a world of retribution and the lost values of an era. But Godard, with his ideas and innovation, assembles the puzzle pieces in such a way that meaning is pushed aside, leaving only the form itself. And in the end, it’s the form that makes the viewer think: How interesting!

A form that has its complexities but doesn’t shout them aloud. Instead, it quietly cools the audience in its shadows: postmodernism.

334 num s